Ucedrah Osby heard the terrible news in a way nobody ever wants to: from a local television report, at the same time as everybody else in Bakersfield, California who tuned in.

“They were doing interviews,” she recalled. “They were saying that the facility had a COVID outbreak.”

Osby’s uncle, Clyde Lee Cooper, 76, lived in Kingston Healthcare Center, the nursing home in question. Over the course of that week in early May as Osby desperately tried to get updates on Cooper’s health, coronavirus engulfed the place. Ambulances arrived, wheeling patients away who never returned.

To date, 104 residents have contracted COVID-19 in a facility with 184 beds, at least 19 have died of the coronavirus, and dozens of staff members have tested positive. Al Jazeera’s Fault Lines reported on the crisis in the elder care system for When COVID Hit: America’s Nursing Home Nightmare.

Kingston Healthcare Center [Al Jazeera]

Kingston Healthcare Center [Al Jazeera]‘This country’s killing fields’

In an industry already infamous for poor care, Osby may be right. The federal government lists Kingston as a “special focus” facility, one that officials monitor due to serious concerns about the quality of care. Most nursing homes receive stars in a government-administered rating system, but Kingston does not because of its status as a troubled operation. So far this year, patients and their families have filed 192 formal complaints against it, compared with the state average of 21.

As COVID numbers soar to record levels past 150,000 daily cases in the United States, nursing homes will likely once again become hotspots where a deadly brew of the winter flu and the coronavirus race through a captive crowd. Most administrators will seek to stop the spread by locking down facilities – isolating an already vulnerable population. They adopt these desperate measures because their patients account for approximately a quarter of all COVID-19 deaths nationwide, some 69,000 people.

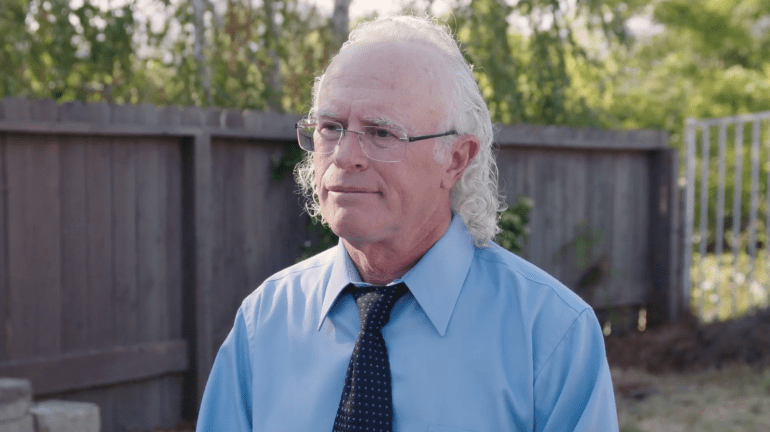

They have become “this country’s killing fields,” said Dr Michael Wasserman, until recently the head of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine.

Michael Wasserman [Screengrab/Al Jazeera]

Michael Wasserman [Screengrab/Al Jazeera]“It’s all about the money,” said Molly Davies, who investigates complaints at facilities for the city and county of Los Angeles. “The staff are not very well paid. You can make just as much or more working at McDonald’s than working as a nursing assistant.”

‘They’re just forgotten’

Christina White, for example, is a longtime nursing assistant at Kingston. “I make 78 cents over the minimum wage along with a lot of other people in our building,” she said. That would equal $13.78 an hour in Kern County, where Kingston is located. Many workers at nursing facilities end up working two jobs to make ends meet.

Christina White [Al Jazeera]

Christina White [Al Jazeera]“Their quality of care was pretty much none,” DeWoody recalled, remembering elderly patients lying for hours without access to water, suffering from a combination of COVID-19 and dehydration. She described others sitting in their urine and faeces, with no one to change them – potentially leading to deadly sepsis, a common condition in nursing homes when patients become infected from their own excrement. As workers stopped showing up, patients would cling to DeWoody’s arm, begging her not to abandon them. She cried on her drive home every day.

“It made me feel small,” she said, describing her sense of helplessness. “These people are left there, you know. Their families couldn’t take care of them any more. A lot of them are left there, and they’re just forgotten.”

Christina DeWoody [Al Jazeera]

Christina DeWoody [Al Jazeera]‘A nightmare you couldn’t wake up from’

Throughout this period, the owner of the Kingston Healthcare Center, Dr David Silver – who lives in the tony Beverly Hills neighbourhood – never once showed up, according to DeWoody and other staff members we spoke to. Over the course of several weeks, Al Jazeera’s Fault Lines reached out to Silver for an interview, eventually trying his office and home. He finally responded by email, pointing out that “no new residents have tested positive for the disease in over 3 months” – which was only after county, state, and federal health officials got involved.

Silver also wrote that “the staff prior to the outbreak underwent extensive training”. According to workers there, however, that training did not include the early adoption of PPE.

“It wasn’t mandated that we start wearing masks until April,” said White, the nursing assistant. “And it was just a surgical mask.”

The coronavirus continued to spread among her coworkers. It was “like a nightmare you couldn’t wake up from.”

Silver owns Kingston Healthcare Center, but a separate company – one he also happens to be CEO of – Rockport Healthcare Services – oversees the facility. This business structure is a common practice in the industry.

“There’s typically multiple ownership layers,” explained Wasserman, the nursing care specialist who himself had once served as CEO of Rockport until he found some of the practices there untenable.

The exterior of Kingston Healthcare Center [Al Jazeera]

The exterior of Kingston Healthcare Center [Al Jazeera]Favouring ‘industry above consumers’

With the buck getting tossed around, authorities find it difficult to hold anyone accountable. But Davies, who has spent her career on elder care issues, points out that the regulatory agency “favours the industry above consumers” as a result of the outsized power of nursing industry players and their lobbying.

Rockport’s application to run nursing homes, for example, is still pending – meaning it has operated without a license in the interim. Wasserman told us this was the case when he assumed the position of Rockport CEO in 2017. When Fault Lines asked about this, the California Department of Public Health said the company “is permitted to operate during the pendency of its application” – the equivalent of waiting for a driver’s license and driving with a provisional paper – for years.

A wxindow visit [Screengrab/Al Jazeera]

A wxindow visit [Screengrab/Al Jazeera]‘No way to live’

That left people like Melody Taylor Stark in distress. Her 84-year-old husband Bill Stark, who had been battling cancer this year, lived in a nursing home. She had hoped lockdown measures would lift by now, so they could spend time together.

The couple has had few opportunities to meet since the spring, maintaining contact only by phone.

“He would be saying this is no way to live,” Stark said. “And he would start crying.”

Stark believes dealing with the isolation was tougher for her husband than dealing with cancer treatment – while she also worried about COVID. She could not understand why the government did not commit more money and assistance to the elderly.

Melody’s husband Bill Stark [Photo courtesy of Melody Taylor Stark]

Melody’s husband Bill Stark [Photo courtesy of Melody Taylor Stark]The last time Stark spoke to her husband was during a video call on November 22. He passed away early the next morning, alone.

He did not die from the novel coronavirus. But the way he died was a consequence of it.

Watch: When COVID Hit: America’s Nursing Home Nightmare

"wait" - Google News

December 03, 2020 at 02:06AM

https://ift.tt/2JBxrtd

‘Where people come to wait to die’: COVID-19 in US nursing homes - Al Jazeera English

"wait" - Google News

https://ift.tt/35qAU4J

https://ift.tt/2Ssyayj

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "‘Where people come to wait to die’: COVID-19 in US nursing homes - Al Jazeera English"

Post a Comment