Julie Mehretu is the most exciting visual artist of our time and an artist who speaks compellingly to our time, not through satire or social realism, as most political artists do, but in abstract images of striking originality. Her paintings—vast canvases, many of them more than a dozen feet long—erupt with volcanic swirls, darting lines, swarms of syncopated ink blots, all in crisscrossing layers of labyrinthine detail.

You can get lost in these worlds, and in that sense, Mehretu prompts comparison with Jackson Pollock. But where Pollock’s brushstrokes were spontaneous outbursts of expression (hence the term “Abstract Expressionism”), Mehretu is, as she once put it, “trying to understand myself … digging deeper into who I am,” in terms of how her own history fits into the history not just of art but of the world.

Given Mehretu’s life story, this “obsession,” as she’s called it, is the opposite of navel-gazing. She was born in 1970 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and fled that country’s civil wars, along with her family, for the calmer but, in its own way, still turbulent climes of Michigan, when she was 7. (She has lived in New York since graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design.) Viewed in this context, almost all of her works are explorations of war, migration, and rebellion: the clash of civilizations and the oppression or resistance of the masses.

This would be merely interesting, at best, if Mehretu’s artworks were symbolic dioramas for studies of imperialism. But she has somehow created a technique, a style, a language to vivify the maelstrom of modernity, its deep layers of underlying time, and the dynamism of the networks and systems that stitch these strands together. The stitching isn’t seamless: There is mystery and madness in this tale, just as, in some of her paintings, there are traces of stairways ascending and stairways descending, brash lines leading nowhere, bold arrows striving toward patterns of motion but stricken by waves of disruption. We, the viewers, remain agents, not mere objects, of this epic. A deep dive into these paintings can be at once horrifying and exhilarating.

A midcareer retrospective of Mehretu’s works—which opens Thursday at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, after runs at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, with one more stop, at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, this fall—traces her artistic and political evolution with thrilling clarity. (The curators are LACMA’s Christine Y. Kim and the Whitney’s Rujeko Hockley.)

The show—some 40 paintings and 30 works on paper, which take up the entirety of the Whitney’s fifth floor—begins with Mehretu’s art-school projects from 1996–97: small, meticulous ink drawings of signs, symbols, and interweaving maps. Already, she was seeking a new language, new patterns, new ways of deciphering the world. (It may be significant that her father was an economic geographer.) In retrospect, these otherwise modest sketches formed the genesis of what was to come.

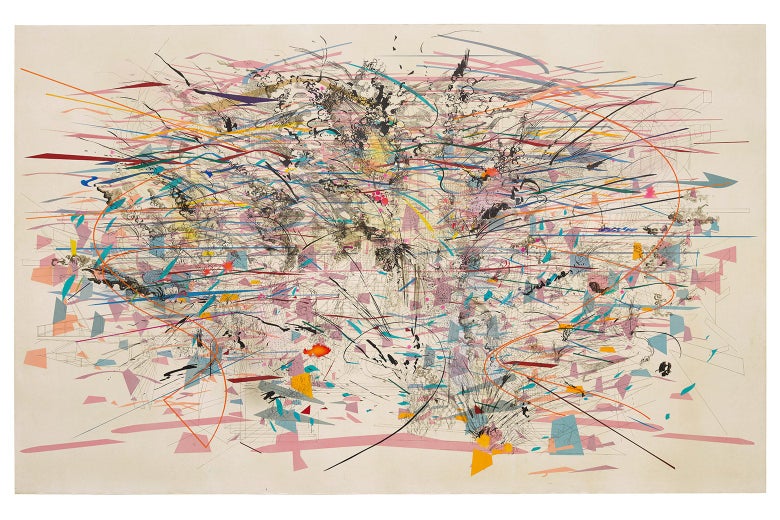

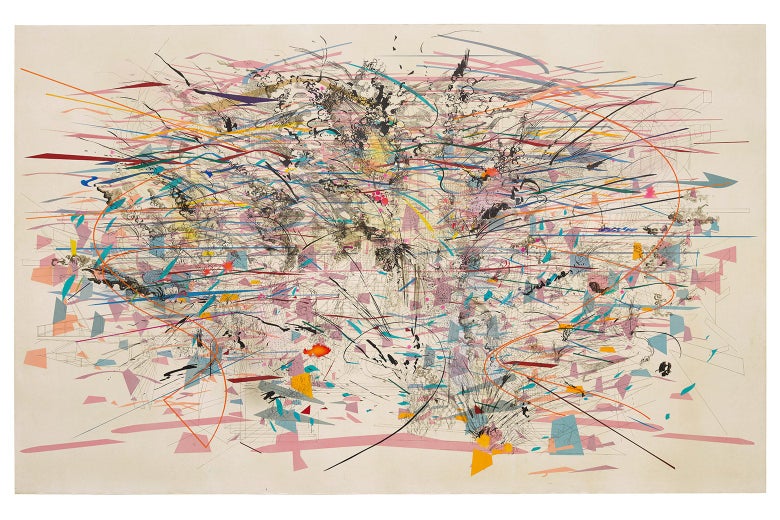

And it came with remarkable speed. By the end of the decade, she was creating her first ink-and-acrylic swirl storms on 6-foot-wide canvases, and just a few years after that, in 2002, she unfurled her first masterpiece, Renegade Delirium, a massive, kaleidoscopic shockwave to the senses, as if every clash, rupture, uprising, and epic ebb and flow in the annals of humanity, across space and time, were somehow compressed and transported, in all their intricacies, to a 7½-by-12-foot canvas. Nothing this side of Pollock’s One: Number 31, 1950 packs the punch of such an artistic Big Bang.

This phase of Mehretu’s career climaxed in 2009, with Mural, an astonishing 80-foot-wide canvas—permanently but privately displayed two miles south of the Whitney, in the lobby of Goldman Sachs, which commissioned the work—that conveys, as Calvin Tomkins has summarized, the “history of finance capitalism—maps, trade routes, population shifts, financial institutions, the growth of cities.”

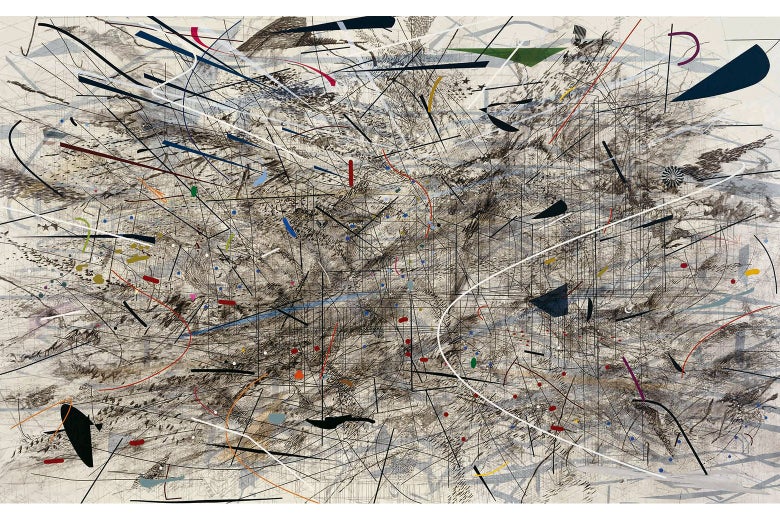

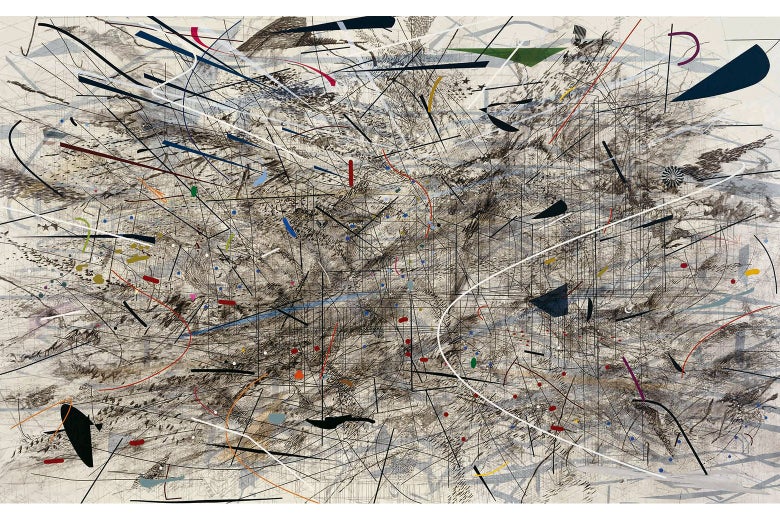

Even before launching into the yearlong project of Mural, Mehretu was evolving into darker, denser landscapes with darker, more pointedly political themes, often stressing more distinctly the architectural layers beneath the explosive swirls. She started the multilayered Black City (2007) with stock drawings of fortified cities through the ages—from Japan and Mesopotamia to Hitler’s Atlantic Wall bunkers—as a comment on repressive trends in American politics. There is a symphonic quality to the work and others from this period. We might not detect the references without the wall plaque, just as it might take a few listens and some program notes to follow all the motifs in a piece of orchestral music, but whether with music or art, the work’s emotional power should transport you, even without a guide—and, looking at Black City, you don’t need a curator’s explication to feel the menace.

This phase of her work intensified, in 2012, with Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts), inspired by the revolts in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. Working with a crew of assistants (a practice she began with the gargantuan Mural), she gathered and digitized drawings, photos, and architectural plans of several public squares where mass protests took place (Tahrir, her native Addis Ababa’s Meskel Square, New York’s Zuccotti Park). Her crew projected and traced them onto a canvas, which Mehretu then covered with her trademark swirls, lines, and markings, more furious and fastidious than ever.

A decade had passed since Renegade Delirium, yet in these four paintings, her most enigmatic up to this point, the role of her small markings takes on a new clarity. They emerge the agents of change and resistance, or the objects of control and oppression, in her vast portraits of civilization’s engines at full throttle—a “battle of small marks in this longview of time,” as she has put it, adding, “The marks are insistent.”

Over the next four years, Mehretu created several works in this mode, depicting uprisings and wars in Syria as well. As with all of her works, they demand to be absorbed from a distance—to take in the big picture, in all the meanings of that phrase—and scrutinized up close, at length. The fusion of historic sweep and minute human drama is stunning. (The exhibition’s catalog, published by the Whitney, allows these dual views, containing not only superbly reproduced images of every work in the show, plus some, but also dozens of life-size full-page highlights from her larger, denser paintings.)

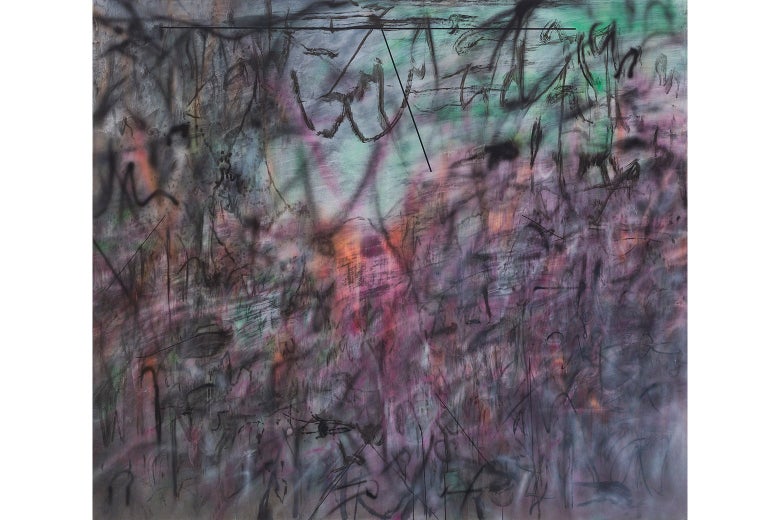

In the past five years, Mehretu has shifted into yet another phase, in some ways her most beautiful and most mystifying. The canvases are still huge (8 to 10 feet wide, or larger), but gone are the architectural underpinnings and the caravans of small marks. Instead, the works begin with photographs, which she digitizes, defocuses, turns at a 90- or 180-degree angle, the results of which she projects and traces onto the canvas, before lavishing them with her acrylic-and-ink slashes and scrawls—now more hieroglyphic, but also more sensuous than before, infused with more vibrant colors, reminiscent of Kandinsky.

The underlying photographs, often taken from news files, are of race riots, forest fires, and other calamities in the headlines of the day. Most striking in this show is Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson. (Her most monumental work in this style—HOWL, eon, a pair of canvases, each measuring 27-by-32 feet, flanking the stairwell at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which commissioned them—began with photos of riots, urban protests, and copies of 19th-century landscape paintings of the American West.)

Gerhard Richter did something like this, a few years earlier, with his Birkenau series, based on four grainy photos that were secretly taken at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp during the Nazi reign. Richter drew the photos, painted the drawings, then scoured the paint with his customary squeegee. These paintings, which were recently displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the first time all four had been shown together in the U.S.), are truly grim; the original images are obscured, but the dread and horror peer through.

Mehretu’s works in this vein are, again, gorgeous paintings, but, in a way, that’s part of the puzzle. I’m not sure if they evoke what she intends to evoke. I doubt that I’d guess that Conjured Parts was inspired by the Ferguson protests, or anything like them, just by looking at it. I do see the connection after reading the wall plaques and straining to look in a different way from before. But shouldn’t a painting, even one diffused of its figurative roots, have some emotional resonance with those roots? (Her earlier works, though also obscure, usually do.)

I don’t know the answer to this question. Mehretu has quoted the remark by Martinican writer and critic Édouard Glissant: “We clamor for the right to opacity for everyone.” And she is certainly entitled. I look forward to pondering the matter further when I revisit her show two, three, or who knows how many times before it closes Aug. 8. And I look forward, even more, to seeing what she does next. This is a “midcareer retrospective,” and Mehretu has packed, unpacked, and metamorphosed more ideas and innovations, more magically, than any artist in many years.

"exciting" - Google News

March 25, 2021 at 04:45PM

https://ift.tt/2PvtvwX

The Swirl of History - Slate

"exciting" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2GLT7hy

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Swirl of History - Slate"

Post a Comment